Chapter 1: Basic of Biology for Biophysics

This chapter provides a brief overview of key events and concepts that have shaped the field of biophysics. We believe that understanding these historical developments is crucial for appreciating the evolution of biophysics beyond merely its current state. While this chapter does not replace the foundational knowledge gained in introductory biology and biochemistry courses, it aims to serve as a quick refresher. For a more in-depth exploration, we encourage readers to revisit relevant materials from their introductory physics courses.

1.1 Introduction

In the 19th century, significant developments in physics led to a deeper understanding of the natural world. Leading figures like Sadi Carnot, William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), James Prescott Joule, and later James Clerk Maxwell made pivotal contributions to the development of thermodynamics. This field of study, which deals with heat, work, and energy, proved to be a cornerstone for many scientific disciplines.

A fundamental principle in science, laws of physics, governs the behavior of all matter and energy in the universe, also apply to biological systems. From the smallest molecules to the largest ecosystems, living organisms operate within the constraints imposed by the laws of physics.

In the modern era, fundamental theories of physics like quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, electromagnetism, mechanics, and optics have been remarkably successful in describing the behavior of non-living systems, ranging from microscopic particles to macroscopic phenomena like solid-state physics and astrophysics. However, these theories sometimes fall short when applied to living systems, necessitating adjustments to better suit biological contexts.

1.2 The Birth of Biophysics and Key Events

Biophysics emerged as a distinct scientific discipline in the mid-20th century, driven by the pioneering work of researchers with backgrounds in physics who began applying their expertise to biological problems. This period saw significant advancements in our understanding of biological molecules, leading to the birth of molecular biology.

Biophysics is inherently interdisciplinary, drawing upon knowledge and techniques from physics, biology, chemistry, mathematics, engineering, and computer science. It seeks to understand fundamental biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels by applying the principles and methods of physics.

Bridging the gap between physics and biology is crucial for gaining deeper insights into life processes. This involves addressing fundamental questions such as:

- How do biological molecules interact and function?

- How do cells form and organize?

- How do living systems operate and evolve over time and space?

Understanding these processes requires a comprehensive approach that considers both spatial and temporal dimensions. The complexity of biological systems poses a significant challenge. However, physics provides a powerful framework for:

- Quantifying biological processes with precision: For example, measuring the rates of biochemical reactions, determining the forces involved in cellular processes, and more.

- Developing sophisticated models to simulate biological systems: For example, using computational models to predict protein structures, simulate cellular signaling pathways, and more.

- Designing and implementing innovative experimental techniques: For example, developing new imaging techniques view biomolecules, creating novel tools for manipulating biomolecules, and utilizing advanced technologies for studying the interactions between biomolecules.

There is a strong coupling between life science analytical tools and experimental physical science techniques. Advances in life science research and biomedicine often rely heavily on various analytical techniques borrowed from the physical sciences, such as microscopy, spectroscopy, and chromatography. These tools are essential for examining biological specimens at different levels, from single molecules to whole organisms. Here are a few tools that have made major breakthroughs in life science:

- DNA Structure : Biophysics played a crucial role in determining the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). In the 1950s, a collaborative effort involving biology, physics, and chemistry led to the resolution of the DNA structure. This involved:

- Biochemical techniques: Purifying and isolating DNA samples.

- Crystallography: Creating highly ordered crystals of DNA fibers.

- X-ray diffraction: Obtaining detailed X-ray diffraction patterns from these crystals.

- Data Analysis: Interpreting the X-ray data to deduce the three-dimensional double-helical structure of DNA.

- Hodgkin and Huxley Model: Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley conducted groundbreaking research on the fundamental mechanisms of nerve impulse conduction, earning them the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1963. Their work, which involved meticulous experimentation and mathematical modeling, revolutionized our understanding of how electrical signals are transmitted along nerve cells, considering the flow of sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+) ions across the nerve cell membrane.

- X-ray Crystallography: X-ray crystallography, a powerful technique developed by physicists, has been instrumental in determining the structures of biological molecules. Dorothy Hodgkin, a pioneering scientist, used X-ray crystallography to elucidate the structures of crucial biomolecules, including cholesterol, penicillin, and vitamin B12. She later extended her work to larger molecules like proteins, culminating in the determination of the structure of insulin. Myoglobin, a protein found in muscle tissue, was also a subject of significant X-ray crystallographic studies.

- Small-angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS): A powerful technique, it is used to investigate material properties at the nanometer scale. Developed in the 1930s, it initially focused on non-biological materials. Over time, SAXS has been successfully adapted to study biological macromolecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids, and protein complexes. SAXS records X-ray scattering at very low angles (typically 0.1° to 5°), providing information about structural features in the range of approximately 1-150 nm. It provides low-resolution information on their shape, conformation, and assembly state. Today, SAXS is considered a valuable biophysical technique for analyzing the structure of biological macromolecules, complementing higher-resolution techniques like X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): This powerful medical imaging technique, invented by physicists, utilizes magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of internal organs and tissues.

- Vibrational Spectroscopy: Typical powerful vibrational spectroscopy techniques include Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy and Raman Spectroscopy.

- FT-IR Spectroscopy : This technique employs mathematical techniques like the Fourier Transform to convert the raw interferogram data into a spectrum. This spectrum represents the absorption or emission of infrared radiation by the sample, which provides information about the vibrational modes of the molecules.

- Raman Spectroscopy : This technique utilizes the inelastic scattering of light by molecules. When light interacts with a molecule, it can be scattered with a slight change in frequency. This frequency shift, known as the Raman shift, provides information about the vibrational energy levels of the molecule.

- Terahertz (THz) Spectroscopy : Traditionally, THz spectroscopy has been used to investigate the properties of condensed matter, such as lattice vibrations and intraband transitions in semiconductors. In recent years, it has emerged as a promising technique for exploring biological systems. THz radiation interacts with the vibrational and rotational modes of biomolecules, providing unique insights into their structure, dynamics, and interactions. This non-destructive technique offers several potential applications in biology, including protein and DNA analysis, drug discovery, medical imaging, and food safety (detecting contaminants). However, its application remains challenging due to the strong absorption of THz radiation by water.

1.3 Fundamentals of Life

Cellular activities are akin to a city’s transportation system. Just as vehicles navigate multiple routes, molecules within a cell participate in various biochemical pathways. However, it’s crucial to remember that cellular processes are far more complex than simple transportation.

1.3.1 The Building Blocks of Life

Only a small subset of the known elements are essential for life:

- Most abundant elements: Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), Oxygen (O), and Nitrogen (N) are the most abundant elements, making up about 96% of our body mass.

- Macronutrients: Other essential elements include Calcium (Ca), Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K), Sulfur (S), Chlorine (Cl), Sodium (Na), and Magnesium (Mg).

- Trace Elements: Trace elements, such as iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn), are required in very small amounts but play crucial roles in various biological processes.

Here are few key function of these elements:

- Oxygen and Hydrogen: The high abundance of these elements is primarily due to the presence of water (H2O).

- Sodium (Na), Potassium (K), and Chloride (Cl): These ions are essential for maintaining proper fluid balance and are crucial for cellular signaling processes.

- Nitrogen (N): Nitrogen is a key component of amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) and nucleic acids (DNA and RNA). Although nitrogen gas (N2) is abundant in the atmosphere, it is relatively inert due to the strong triple bond between the nitrogen atoms.

- Calcium (Ca): Calcium plays vital roles in various physiological processes, including bone formation, muscle contraction, nerve signaling, and cell division.

- Phosphorus (P): Phosphorus is primarily found in the form of phosphates, which are essential components of DNA, RNA, and ATP (the energy currency of cells).

1.3.2 The Role of Carbon:

Carbon is a unique element that serves as the fundamental building block for most biomolecules. The versatility and key features of carbon include:

- Formation four covalent bonds: Carbon atoms have four valence electrons, which typically arrange themselves in a tetrahedral configuration. This allows carbon to create a diverse array of stable and complex molecules with various shapes and sizes.

- Bonding Flexibility: Carbon readily forms stable covalent bonds with itself and other elements such as H, O, N, and S. This ability to form diverse bonds enables the construction of a vast array of biomolecules with varying shapes, sizes, and functionalities.

- Bonding Types:

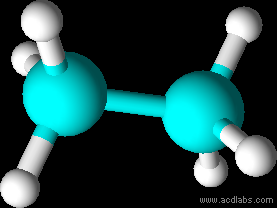

- Single Bonds (C-C): These bonds exhibit free rotation, Fig 1-1b, allowing for flexibility in the three-dimensional structure of molecules.

- Double Bonds (C=C): These bonds are shorter and exhibit restricted rotation, Fig-1-1c, introducing rigidity into molecular structures. Triple Bonds (C≡C): While less common in biomolecules, triple bonds do exist in certain compounds.

- Energy Storage: Carbon compounds such as carbohydrates and lipids, serve as excellent sources of energy storage in living organisms.

Why Carbon and Not Silicon?

While silicon shares some similarities with carbon (both have four valence electrons), carbon is better suited for life as we know it.

Silicon’s larger size and mass: Silicon atoms are larger and heavier than carbon atoms. This leads to:

- Lower bond energies: Silicon-based compounds tend to be less stable and more reactive than carbon-based compounds.

- Lower solubility: Silicon compounds are generally less soluble in water, which is essential for many biological processes.

The importance of a liquid medium: Life as we know it requires a liquid environment for rapid biochemical reactions and the efficient transport of molecules. Water, with its unique properties, is an ideal solvent for carbon-based life. Silicon-based life, if it exists, would likely require a different solvent and potentially different environmental conditions.

1.4 Biomolecules

Even seemingly simple biomolecules are composed of multiple parts. Larger biomolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, exhibit intricate structures. Moreover, living cells themselves are astonishingly complex entities.

1.4.1 Small Biomolecules

Most smaller molecules can be divided into four classes (note each class contains many members): Amino Acids, Carbohydrates, Nucleotides, and Lipids.

- Amino Acids: The simplest compounds are amino acids, named because they contain an amino group (\(-NH_2\)) and a carboxylic acid group (-COOH). Under physiological conditions, these groups are actually ionized to \(-NH_3^+\) and \(-COO^-\).

- Carbohydrates: Simple carbohydrates (also called monosaccharides or just sugars) have the formula \((CH_2 O)_n\) where n≥3 . Glucose, a monosaccharide \(C_6 H_12 O_6\), is a prime example. While often represented as a linear chain, glucose predominantly exists in a cyclic form in solution. Polysaccharides are complex carbohydrates formed by the linkage of multiple monosaccharide units.

- Nucleotides: Nucleotides consist of three core components (Fig): a five-carbon sugar (ribose or deoxyribose), a nitrogenous base (adenine, guanine, cytosine, thymine, or uracil), and one or more phosphate groups. Nucleotides are the fundamental building blocks of DNA and RNA. The most common nucleotides are mono-, di-, and tri-phosphates containing the nitrogenous bases adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, or uracil (abbreviated A, C, G, T, and U).

- Lipids: These compounds, often referred to as fats, cannot be described by a single structural formula since they are a diverse collection of molecules. However, they all share a tendency to be poorly soluble in water because the bulk of their structure is hydrocarbon-like.

1.4.2 Marcromolecules: Building Blocks

Macromolecules are large, complex molecules composed of thousands, or even millions, of atoms. These molecules are not synthesized in a single step but are assembled from smaller, simpler subunits called monomers. When monomers are chemically bonded together, they form polymers, which are the foundation of macromolecules.

Polymerization, the process of linking monomers into polymers, is a fundamental mechanism in the emergence and sustainability of life. This stepwise assembly enables the creation of large, complex structures from a limited set of building blocks. For example, nucleotides form DNA and RNA, amino acids form proteins, and monosaccharides form polysaccharides. This modular approach is highly advantageous for cells, as it allows for the construction of diverse macromolecules using a relatively small repertoire of raw materials.

An essential feature of many biological monomers is their polarity, meaning they have distinct ends often referred to as a “head” and a “tail.” This directionality is crucial in determining the structure and function of the resulting polymers. For instance:

- Proteins: Proteins are polymers formed by the polymerization of amino acids through peptide bonds, creating long chains known as polypeptides. The specific sequence of amino acids, dictated by genetic information, determines the protein’s unique three-dimensional structure and biological function. This structure is organized into four levels: primary structure, secondary structure, tertiary stucture, and quaternary structures.

- Nucleic Acids: Nucleic acids are polymers composed of monomers called nucleotides, which consist of a nitrogenous base (adenine, thymine/uracil, cytosine, guanine), a sugar (ribose or deoxyribose), and a phosphate group. Nucleic acids are essential for storing, transmitting, and expressing genetic information:

- DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid): The primary genetic material in most organisms, DNA stores genetic information in a stable, double-stranded helix. Its structure is stabilized by complementary base pairing (A-T, C-G) via hydrogen bonds.

- RNA (ribonucleic acid): A versatile molecule involved in various aspects of gene expression and regulation. RNA is typically single-stranded and exhibits diverse functions, including:

- mRNA (messenger RNA): Carrying genetic information from DNA to ribosomes for protein synthesis.

- tRNA (transfer RNA): Delivers specific amino acids to the ribosome during protein synthesis, aligning them according to the mRNA sequence.

- rRNA (ribosomal RNA): A structural and functional component of ribosomes, facilitating protein synthesis.

The genetic code: A Near-Universal Language: The genetic code consists of a set of triplet codons, where each codon (a sequence of three nucleotides) corresponds to a specific amino acid or a stop signal. This code is remarkably universal, meaning it is essentially the same in all living organisms, from bacteria to humans. This universality is a strong testament to the early evolution of life and the powerful constraints of natural selection.

The RNA World Hypothesis: A Leading Theory of Life’s Origins Modern theories of the origin of life suggest that RNA, rather than proteins or DNA, may have been the first genetic molecule in early life forms. This idea is supported by the RNA World Hypothesis, which posits that RNA played a dual role as both a carrier of genetic information and a catalyst for biochemical reactions.

- Polysaccharides: These are long-chain polymers made up of monosaccharide units (simple sugars, such as glucose) linked together by glycosidic bonds. Polysaccharides serve a variety of essential biological functions, including energy storage, structural support, and cell-cell interactions.

1.5 Functional Groups in Biomolecules

Biomolecular reactions are governed by organic chemistry, which classifies compounds based on their functional groups. These groups define a molecule’s reactivity and chemical behavior, serving as the primary sites for biochemical interactions.

Understanding functional groups is essential in fields such as bioconjugation, where amines, thiols, carboxyls, and hydroxyls are selectively modified to attach biomolecules to surfaces or other molecules. These modifications are fundamental to biomedical research, diagnostics, and therapeutic applications.

Biomolecules—including nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids—are characterized by their functional groups, which dictate chemical properties, biological roles, and interactions. For example:

- Proteins rely on amine (-NH₂), carboxyl (-COOH), and thiol (-SH) groups for peptide bond formation, enzymatic activity, and structural stability.

- Nucleic acids feature phosphate (-PO₄) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups, crucial for sugar-phosphate backbone formation and hydrogen bonding in base pairing.

- Carbohydrates contain hydroxyl (-OH) and carbonyl (>C=O) groups, enabling water solubility, energy storage, and cell signaling.

- Lipids consist of hydrophobic alkyl chains and hydrophilic head groups, providing membrane structure and energy reserves.

Many biologically significant functional groups contain electronegative atoms such as oxygen and nitrogen, which create polar bonds that enhance chemical reactivity. This polarity facilitates interactions with other polar molecules or ions, a key factor in enzymatic catalysis, molecular recognition, and energy transfer. Examples include hydroxyl (-OH), amine (-NH₂), carbonyl (>C=O), and carboxyl (-COOH) groups.

While alkyl halides and acyl chlorides are valuable in organic synthesis for forming carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bonds, their direct roles in biochemistry are limited due to their high reactivity and instability in aqueous environments. However, modified derivatives, such as activated esters, are employed in bioconjugation and drug delivery systems.

Below is a table summarizing common functional groups found in organic and biological chemistry:

| Class of Compound | Characteristic Group | Name of Functional Group | General Structure | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Hydroxyl | Hydroxyl | R-OH | Ethanol (CH3CH2OH) |

| Aldehyde | Carbonyl | Aldehyde | R-CHO | Formaldehyde (HCHO) |

| Ketone | Carbonyl | Ketone | R-CO-R’ | Acetone (CH3COCH3) |

| Carboxylic Acid | Carboxyl | Carboxyl | R-COOH | Acetic acid (CH3COOH) |

| Ester | Ester | Ester | R-COO-R’ | Methyl acetate (CH3COOCH3) |

| Ether | Ether | Ether | R-O-R’ | Diethyl ether (CH3CH2OCH2CH3) |

| Amine | Amino | Amino | R-NH2 | Methylamine (CH3NH2) |

| Amide | Amide | Amide | R-CONH2 | Acetamide (CH3CONH2) |

| Thiol | Sulfhydryl | Thiol | R-SH | Ethanethiol (CH3CH2SH) |

| Alkene | Double bond | Alkenyl | R-CH=CH-R’ | Ethene (CH2=CH2) |

| Alkyne | Triple bond | Alkynyl | R-C≡C-R’ | Ethyne (C2H2) |

| Halide | Halogen atom | Halogen | R-X (X = F, Cl, Br, I) | Chloroethane (CH3CH2Cl) |

| Nitrile | Cyano | Cyano | R-C≡N | Acetonitrile (CH3CN) |

| Phosphate | Phosphate | Phosphoryl | R-O-PO3H2 | Glucose-6-phosphate |

| Sulfate | Sulfate | Sulfate | R-O-SO3H | Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) |

1.6 Units Used in Biomolecules

- Mass: The standard unit for the mass of biomolecules is the dalton (Da), which is equivalent to one atomic mass unit (amu). By definition, 1 Da is 1/12th the mass of a carbon-12 atom, approximately 1.6605 × 10⁻²⁷ kg. For macromolecules such as proteins, masses are often expressed in kilodaltons (kDa), 1 kDa = 1000 Da.

Protein molecular weights typically range from a few kDa to several thousand kDa. For instance, hemoglobin has a molecular mass of about 64 kDa, while large macromolecular complexes like ribosomes can exceed 2,500 kDa.

- Concentration: Concentrations of biomolecules are typically measured in molarity (M), which represents moles of solute per liter of solution. Common concentration units include:

- millimolar (mM): 1 mM = \(10^{-3}\) M

- micromolar (µM): 1 µM = \(10^{-6}\) M

- nanomolar (nM): 1 nM = \(10^{-9}\) M

- picomolar (pM): 1 pM = \(10^{-12}\) M

- femtomolar (fM): 1 fM = \(10^{-15}\) M

For example, typical cellular concentrations of enzymes and signaling molecules often fall within the nanomolar to micromolar range.

- Distance: Biomolecular structures and interactions are often measured in:

- Angstroms (Å): 1 Å = \(10^{-10}\) meters

- Nanometers (nm): 1 nm = \(10^{-9}\) meters

Notable examples: Covalent bond lengths typically range from 1.2 to 1.5 Å. The diameter of a DNA double helix is approximately 2 nm (or 20 Å). Protein domains typically range from 3 to 10 nm in size.