Chapter 2: Water: The Solvent for Biochemical Reaction

This chapter provides a brief desribtion of water molecules that required for biochemical reaction.

2.1 Introduction

Solvents play a fundamental role in biochemical reactions by providing the medium in which these reactions occur. The choice of solvent significantly influences reaction rates, equilibrium, specificity, and overall efficiency. In biological systems, water is the predominant solvent due to its unique chemical properties, including high polarity, extensive hydrogen bonding capability, broad thermal and pH stability, natural abundance, and and exceptional ability to dissolve a wide range of biomolecules. These properties make water essential for maintaining the structural integrity and function of biomolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and enzymes. Water constitutes approximately 70% of cellular content on average, with variations depending on the cell type and physiological state. Cells generally require a minimum water content of around 60% to sustain normal metabolic activity, emphasizing its critical role in sustaining life.

While water serves as the universal biological solvent, certain biochemical applications require alternative solvents to optimize reaction conditions. Non-aqueous solvents such as organic solvents, ionic liquids (ILs), supercritical fluids (SCFs), and deep eutectic solvents (DESs) are being increasingly explored for their applications in synthetic biology, biocatalysis, and pharmaceutical research. These solvents enable reactions that are inefficient or impossible in aqueous environments. For example, organic solvents like ethanol and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) are commonly used as cryoprotectants, drug delivery enhancers, and solubilizing agents for hydrophobic molecules in biochemical studies and pharmaceutical formulations.

Solvents contribute to biochemical reactions in several key ways:

- Dissolution of Reactants and Products: Solvents facilitate molecular interactions by dissolving reactants and products, ensuring efficient reaction progress. I In aqueous environments, solubility is essential for enzymatic catalysis, metabolic pathways, and intracellular transport mechanisms.

- Stabilization of Intermediates: Many biochemical reactions involve unstable intermediates that require solvent stabilization to proceed effectively. For example:

- Water’s Role: Water stabilizes charged intermediates through hydrogen bonding, dielectric screening (reducing electrostatic interactions between charges), and other electrostatic interactions.

- Alternative Solvents: Ionic liquids (ILs) and deep eutectic solvents (DESs) are being explored for stabilizing biomolecules and enzymes in non-aqueous or specialized environments. It’s important to avoid implying that ILs and DESs always stabilize biomolecules; the effect depends on the specific IL/DES and biomolecule.

Influence on Reaction Kinetics: Solvents affect reaction rates by influencing activation energy, molecular mobility, and diffusion.

- Polar Solvents: Polar solvents like water can enhance reaction rates by stabilizing charged transition states (the highest energy point in a reaction pathway).

- *Nonpolar Solvents: Nonpolar solvents may slow reactions involving charged species because they don’t stabilize the charges as well.

- Maintenance of Proper Reaction Conditions: Solvents help maintain optimal reaction conditions, including temperature, pH, and ionic strength, which are crucial for enzymatic activity and biochemical equilibrium. Some alternative solvents, such as ILs and SCFs, offer tunable properties that enable precise control over reaction conditions in engineered systems.

The choice of solvent is a critical determinant of reaction feasibility, efficiency, and selectivity in both natural and engineered biochemical processes. Researchers are actively exploring alternative “green” solvents that aim to reduce environmental impact and toxicity while enhancing reaction efficiency and sustainability. However, it is important to recognize that no single solvent perfectly balances all desirable properties, and the selection process often involves trade-offs between solubility, stability, reactivity, and environmental considerations.

2.2 Polarity

Electronegativity refers to an atom’s tendency to attract electrons in a chemical bond. A higher electronegativity indicates a stronger pull on electrons, leading to partial negative and positive charges on bonded atoms. The difference in electronegativity between atoms determines bond polarity.

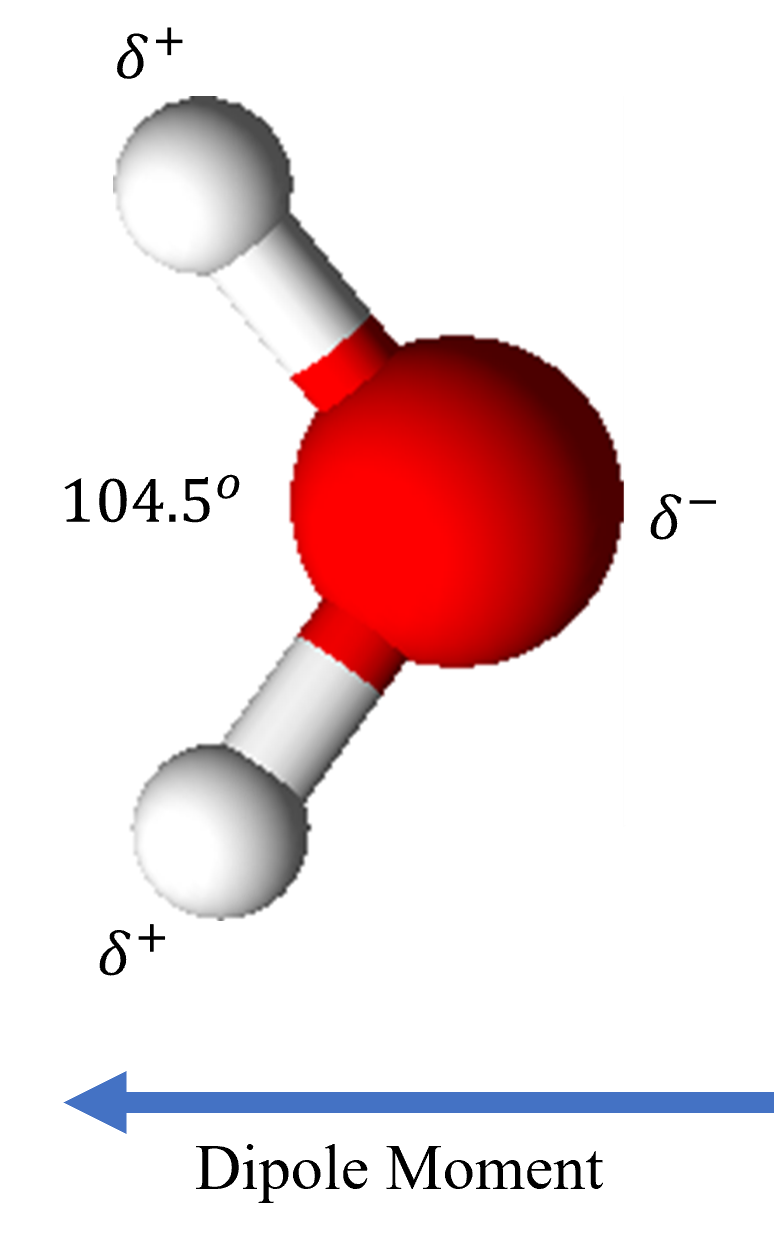

In water (H₂O), the significant electronegativity difference between oxygen and hydrogen results in polar covalent bonds. Oxygen, being more electronegative, carries a partial negative charge (δ⁻), while hydrogen atoms carry partial positive charges (δ⁺). Water’s polarity arises from both this electronegativity difference and its bent molecular geometry, which prevents bond dipoles from canceling, creating a net dipole moment (Figure 1). This polarity enables water to dissolve many substances, particularly polar compounds, through hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions. However, nonpolar substances, such as oils, do not readily dissolve in water, limiting its designation as a “universal solvent.”

Highly electronegative elements like oxygen, nitrogen, and fluorine strongly attract electrons in chemical bonds (Table 1). When atoms with a significant electronegativity difference bond, electron distribution becomes uneven, forming a polar bond. Conversely, when the difference is small, as in C-H bonds in methane (CH₄), electrons are shared more equally, making the bond nonpolar.

Table 1: Electronegativity of Common Elements

| Element | Electronegativity (Pauling Scale) |

|---|---|

| Fluorine | 3.98 |

| Oxygen | 3.44 |

| Nitrogen | 3.04 |

| Chlorine | 3.16 |

| Bromine | 2.96 |

| Iodine | 2.66 |

| Carbon | 2.55 |

| Sulfur | 2.58 |

| Hydrogen | 2.20 |

| Phosphorus | 2.19 |

It is important to distinguish bond polarity from molecular polarity. A molecule can contain polar bonds yet be nonpolar overall if its shape leads to a symmetrical charge distribution. For example, while each C=O bond in carbon dioxide (CO₂) is polar, its linear geometry causes the dipoles to cancel, making the molecule nonpolar (Figure 2).

2.3 Bonding Mechanisms in Biomolecules

This section discusses the major bonding mechanisms within biomolecules and their interactions with the surrounding solvent. Four primary types of bonds and interactions are crucial for biomolecular structure and function: covalent bonds, ionic bonds, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals forces. Additionally, hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions play a significant role, though they are not bonds in the traditional sense but rather reflect the interplay between biomolecules and water. Table 2 presents the bond strengths (in kJ/mol) associated with interactions involving hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms.

Table 2: Bond Strength of Various Bond Types Involving H and O Atoms.

| Bond Type | Strength (kJ/mol) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| O–H Covalent Bond | 400 – 460 | Strong bond formed by shared electrons between O and H (e.g., in water). |

| O–H Ionic Bond | 40 – 200 | Arises when O or H exist as ions (e.g., hydroxide, hydronium, carboxylate). Strength varies based on specific ions. |

| O–H Hydrogen Bond | 10 – 40 | Weak interaction between an O–H group and an electronegative atom (e.g., O, N, F in water, alcohols). |

| van der Waals (O & H) | 0.1 – 10 | Weak, transient dipole-dipole interactions that can occur between any atoms, including those in O–H groups. |

The following subsections will explore each of these interactions in detail.

2.3.1 Covelent Bonding

Covalent bonds, formed by the sharing of electrons between atoms, are strong and essential for holding molecules together. Rather than exploring the general principles of covalent bonding, we will focus on three key types crucial in biological systems, each discussed in detail in separate chapters:

- Peptide Bonds: These bonds link amino acids together to form proteins.

- Glycosidic Bonds: These bonds connect monosaccharides (simple sugars) to form carbohydrates.

- Phosphodiester Bonds: These bonds form the backbone of nucleic acids, DNA and RNA.

2.3.2 Ionic Bonds

Ionic bonds are electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged ions or groups. They are indeed important in protein folding and enzyme-substrate interactions. However, their significance extends beyond these examples. Ionic bonds also play crucial roles in other biological processes, such as maintaining DNA structure and contributing to the stability of cell membranes. We will explore ionic bonds in more detail within the context of protein folding, as well as other relevant biological processes where they play a key role.

2.3.3 Hydrogen Bonding

A hydrogen bond is a relatively weak non-covalent interaction that occurs between a hydrogen atom—covalently bound to a highly electronegative atom (such as oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), or fluorine (F))—and another electronegative atom. The atom to which the hydrogen is directly bonded is referred to as the hydrogen-bond donor, while the electronegative atom that interacts with the hydrogen is the hydrogen-bond acceptor.

The strength of a hydrogen bond is influenced not only by the electronegativity of the participating atoms but also by factors such as bond distance, orientation, and the surrounding environment. Hydrogen bonding plays a fundamental role in many chemical and biological systems.

Table 3 compares hydrogen bonding in hydrogen fluoride (HF), water (H₂O), and ammonia (NH₃), highlighting variations in bond strength and molecular interactions.

Table 3: Hydrogen Bond Strengths in Select Molecules

| Molecule | Hydrogen Bond Strength (kJ/mol) | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF | ~29 | Strongest due to high electronegativity of F | |

| H₂O | ~20 | Moderate strength, essential for life | |

| NH₃ | ~13 | Weakest due to lower electronegativity of N |

Hydrogen bonds are crucial for several biological and chemical processes, including:

- Solubility of biomolecules in water: Polar biomolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, enhancing their solubility.

- Stabilizing DNA double helix: Complementary base pairs in DNA (adenine-thymine (A-T) and guanine-cytosine (G-C)) are held together by hydrogen bonds, contributing to the structural integrity of the double helix.

- Maintain protein secondary structures: Hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms stabilize secondary structural elements such as α-helices and β-sheets, which are essential for protein function and stability.

Hydrogent Bonds in Water: : Water molecules form extensive hydrogen bond networks due to oxygen’s high electronegativity and the presence of two lone pairs. Each water molecule can act as both a hydrogen bond donor (via its two hydrogen atoms) and a hydrogen bond acceptor (via its two lone pairs), allowing it to form up to four hydrogen bonds. The partially positive hydrogen atoms are attracted to the partially negative oxygen atoms of neighboring water molecules. Linear hydrogen bonds (where the O-H···O atoms are aligned) are generally stronger than bent hydrogen bonds, although the difference in bond energy is moderate (~1–2 kJ/mol) (see Figure 3).

Water’s unique density behavior is a direct consequence of hydrogen bonding. In ice, each water molecule forms four hydrogen bonds in a tetrahedral arrangement, resulting in an open hexagonal lattice (Figure). This structure increases the intermolecular spacing, making ice less dense than liquid water and allowing it to float.

In liquid water, hydrogen bonds are highly dynamic and short-lived. While each molecule can still form hydrogen bonds with up to four other molecules, these bonds continuously break and reform. The average lifetime of a hydrogen bond in liquid water is 1–10 ps (10⁻¹² s), while the timescale for breaking and reforming a hydrogen bond is approximately 0.1 to 1 picoseconds (10⁻¹³ to 10⁻¹² s) at 25°C. Unlike the rigid hexagonal lattice of ice, liquid water exhibits a fluctuating network where transient clusters—such as flickering six-membered rings—form and dissolve rapidly (Figure).

Additionally, the absence of hydrogen bonding in molecules such as methane (CH₄) and hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) explains why they exist as gases at room temperature, despite having molecular masses comparable to water. In contrast, water (H₂O) exhibits strong hydrogen bonding, significantly increasing its boiling point compared to CH₄ and H₂S (see Table 4).

Table 4: Comparison of Molecular Mass and Boiling Points

| Molecule | Molecular Mass (g/mol) | Boiling Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| H₂O | 18 | 100 |

| CH₄ | 16 | -161.5 |

| H₂S | 34 | -60 |

Methane (CH₄), despite being smaller in mass than water, lacks hydrogen bonding and relies only on weak van der Waals (London dispersion) forces, leading to its extremely low boiling point (-161.5°C). Similarly, hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) has a higher molecular mass than water but still lacks strong hydrogen bonding because sulfur is less electronegative than oxygen, making H₂S a gas at room temperature (-60°C). In contrast, water’s extensive hydrogen bonding network results in a much higher boiling point (100°C), allowing it to remain a liquid under standard conditions.

2.3.4 Van der Waals Interactions

Van der Waals forces, named after Dutch physicist Johannes Diderik van der Waals, are weak, short-range, non-covalent interactions essential for the structure, stability, and function of biomolecules. These forces arise from transient dipoles generated by fluctuations in electron distributions and are generally categorized into three main types:

- London dispersion forces (induced dipole-induced dipole interactions): These occur due to instantaneous dipoles in nonpolar molecules, such as interactions between methyl groups. Although individually weak, their cumulative effect in larger systems can surpass other van der Waals interactions. The strength of London dispersion forces increases with molecular size and polarizability.

- Dipole-dipole interactions: These arise between molecules with permanent dipole moments, where the positive end of one molecule is electrostatically attracted to the negative end of another. Their strength depends on the magnitude of the dipoles and the intermolecular distance, varying widely with molecular structure.

- Dipole-induced dipole interactions: Occur when a polar molecule with a permanent dipole induces a temporary dipole in a neighboring nonpolar molecule by distorting its electron cloud.

Despite their individual weakness, van der Waals forces collectively play pivotal roles in various biological processes:

- Protein folding and stability: Van der Waals interactions contribute to the tight packing of amino acid side chains within the hydrophobic core of proteins, ensuring proper folding, minimizing void spaces, and enhancing structural integrity.

- DNA Structure: Base stacking in DNA is stabilized by van der Waals forces, particularly through π–π interactions between adjacent nucleobases. While hydrogen bonding is often emphasized, van der Waals forces are equally vital for maintaining the DNA double helix’s stability.

- Ligand-Receptor Binding: These forces facilitate molecular recognition events, such as enzyme–substrate binding and drug–target interactions. Though individually weak, their cumulative effect across multiple contact points significantly enhances binding affinity and specificity.

In summary, while van der Waals forces are individually weak, their collective contribution is substantial, influencing biomolecular processes ranging from protein folding and DNA stability to molecular recognition and binding.

2.3.5 Hydrophoic and Hydrophilic Effects

Water dissolves many compounds: water molecules are able to form hydrogen bonds and participate in other electrostatic interactions with a wide variety of compounds. Water has a relatively high dielectric constant.

The polar water molecules surround ions (for example, the Na^+ and Cl^- ions from the salt NaCl) by aligning their partial charges with the oppositely charged ions (Fig-2.7 (Left)). Biological molecules that bear polar or ionic functional groups are also readily solubilized, in this case because the groups can form hydrogen bonds with the solvent water molecules (Fig-2.7 (Right))

Glucose and other readily hydrated substances are said to be hydrophilic (water-loving). In contract, a compound such as dodecane (a C_12 alkane) which lacks polar groups, is relatively insoluble in water and is said to be hydrophobic (water-fearing).

Nonpolar molecules tend to clump together, removing themselves from contact with water molecules. (This explains why small oil droplets coalesce into one large oily phase.) Although the entropy of the nonpolar molecules is thereby reduced, this thermodynamically unfavorable event is more than offset by the increase in the entropy of the water molecules, which regain their ability to interact freely with other water molecules. Cell maintains the high and low concentrations of K+ and Na+ using Na/Ka pumps. (channel)

Role of entropy in hydrophobic and hydrophilic effect.

The association of a relatively nonpolar molecule or group with other nonpolar molecules is termed a hydrophobic interaction. Although hydrophobic interactions are sometimes called hydrophobic “bonds,” this description is incorrect. Nonpolar molecules don’t aggregate because of mutual attraction but because the polar water molecules surrounding them tend to associate with each other rather than with the nonpolar molecules. Micelles (Figure) are stabilized by hydrophobic interactions.

2.4 Acids and Bases

Water ionization generates hydrogen ions (H⁺) and hydroxide ions (OH⁻), which play a vital role in shaping the structure and function of biomolecules, including proteins, nucleic acids, phospholipids, and cellular membranes. These ionization properties significantly impact enzymatic activity, molecular interactions, and cellular homeostasis, making them essential for biological processes.

2.4.1 Weak Acids and Dissociation Constants

Weak acids and bases are defined by their dissociation constants. Unlike strong acids and bases such as HCl and NaOH, which dissociate completely in water, most biologically relevant acids and bases only partially dissociate. This means that proton transfer to or from water occurs to a limited extent.

For example, the dissociation of acetic acid (CH$_3$COOH) in water can be described by the following equilibrium reaction:

\[\begin{equation} \text{CH}_3\text{COOH} + \text{H}_2\text{O} \rightleftharpoons \text{CH}_3\text{COO}^- + \text{H}_3\text{O}^+ \tag{2.1} \end{equation}\]The equilibrium constant, K, for this reaction is defined as:

\[\begin{equation} K = \frac{[\text{CH}_3\text{COO}^-][\text{H}_3\text{O}^+]}{[\text{CH}_3\text{COOH}][\text{H}_2\text{O}]} \tag{2.2} \end{equation}\]However, since the concentration of the concentration of water ([H₂O]) is exceptionally high and remains nearly constant. It’s often incorporated into the equilibrium constant, resulting in the acid dissociation constant, \(K_a\):

\[\begin{eqnarray} K_a &=& \frac{[\text{CH}_3\text{COO}^-][\text{H}_3\text{O}^+]}{[\text{CH}_3\text{COOH}]} \\ &=& \frac{[\text{CH}_3\text{COO}^-][\text{H}^+]}{[\text{CH}_3\text{COOH}]} \tag{2.3} \end{eqnarray}\]For acetic acid, the acid dissociation constant is:

\[\begin{equation} K_a = 1.74 \times 10^{-5} \tag{2.5} \end{equation}\]The acid dissociation constant, \(K_a\), directly measures an acid’s strength. A larger \(K_a\) indicates a stronger acid with a greater tendency to donate protons, whereas a lower \(K_a\) signifies a weaker acid and reduced proton donation.

Because \(K_a\) values are often very small, it is convenient to express them on a logarithmic scale using pKa:

\[\begin{equation} pK_a = -\log K_a \tag{2.6} \end{equation}\]For instance, the \(pK_a\) of acetic acid is:

\[\begin{equation} pK_a = -\log(1.74 \times 10^{-5}) = 4.76 \tag{2.7} \end{equation}\]The ammonium ion (\(NH_4^+\)) acts as a weak acid, donating a proton in aqueous solution according to the following equilibrium:

\[\begin{equation} NH_4^+ \rightleftharpoons NH_3 + H^+ \tag{2.8} \end{equation}\]Where \(K_a=5.62×10^{-10}\) and corresponds to a pK is 9.25.

Note the inverse relationship: a higher \(K_a\) results in a lower \(pK_a\), indicating a stronger acid. Therefore, \(pK_a\) serves as a valuable index for expressing the acidity of weak acids.

Table 4: pKa Values of Selected Acids

Table 4: pKa Values of Selected Acids

| Acid | Chemical Formula | pKa Value(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic Acid | CH₃COOH | 4.76 | |

| Formic Acid | HCOOH | 3.75 | |

| Benzoic Acid | C₆H₅COOH | 4.20 | |

| Carbonic Acid | H₂CO₃ | 3.6 (pKa1), 10.3 (pKa2) | |

| Citric Acid | C₆H₈O₇ | 3.13 (pKa1), 4.76 (pKa2), 6.40 (pKa3) | |

| Ammonium Ion | NH₄⁺ | 9.25 | |

| Lactic Acid | CH₃CH(OH)COOH | 3.86 | |

| Phosphoric Acid | H₃PO₄ | 2.15 (pKa1), 7.20 (pKa2), 12.35 (pKa3) | |

| Hydrofluoric Acid | HF | 3.18 | |

| Dihydrogen Phosphate | H₂PO₄⁻ | 7.20 (pKa2 of Phosphoric Acid) | |

| Hypochlorous Acid | HOCl | 7.53 | |

| Nitrous Acid | HNO₂ | 3.30 | |

| Sulfurous Acid | H₂SO₃ | 1.86 (pKa1), 7.21 (pKa2) | |

| Phenol | C₆H₅OH | 9.90 | |

| Hydrogen Phosphate | HPO₄²⁻ | 12.35 (pKa3 of Phosphoric Acid) |

The dissociation of acetic acid (HAc) in water can be represented as: $$\begin{equation} HAc \rightleftharpoons H^+ + Ac^- \end{equation}$$ where \(Ac^-\) represents the acetate ion \(CH_3COO^-\). In solution, some amount 𝑥 of HAc dissociates, producing 𝑥 moles of \(Ac^-\) and an equal amount of \(H^+\). Since ionic equilibrium is established rapidly, the total concentration of \([HAc]\) + \([Ac^-]\) remains 0.1 M at equilibrium. Thus, the concentrations can be expressed as: $$\begin{eqnarray} [HAc] &=& (0.1 - x) M \\ [Ac^-] &=& [H^+] = x M \\ \end{eqnarray}$$ Using the acid dissociate constant \(K_a\) for acetic acid: $$\begin{equation} K_a = \frac{[H^+][Ac^-]}{[HAc]} = 1.74 \times 10^{-5} M \end{equation}$$ Substituting the equilibrium concentrations: $$\begin{equation} \frac{[x^2]}{[0.1-x]} = 1.74 \times 10^{-5} M \end{equation}$$ Since \(K_a\) is small, we can approximate \(0.1-x \approx 0.1\), simplifying the equation to: $$\begin{equation} \frac{x^2}{0.1} = 1.74 \times 10^{-5} M \end{equation}$$ Solving for x: $$\begin{equation} x = 1.32 \times 10^{-3} M \end{equation}$$ Since \([H^+] = x \), we calculate the pH: $$\begin{equation} pH = - \log (1.32 \times 10^{-3}) \end{equation}$$ Thus, the pH of a 0.1 M acetic acid solution is 2.88.