Chapter 4: Model of Atoms

The goal of this chapter is to explore the fundamental structure of the atom and understand the nature of matter by examining key experiments and discoveries that shaped modern atomic theory. We will begin by delving into J.J. Thomson’s cathode ray tube experiment, which led to the groundbreaking discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be identified. Next, we will investigate Ernest Rutherford’s gold foil experiment, an ingenious scattering study that revealed the existence of the nucleus and the distribution of electric charge within the atom. Finally, we will introduce the Rutherford-Bohr model, often simply called the Bohr model, which provides a simplified yet powerful framework for describing atomic structure and energy levels.

4.1 Introduction

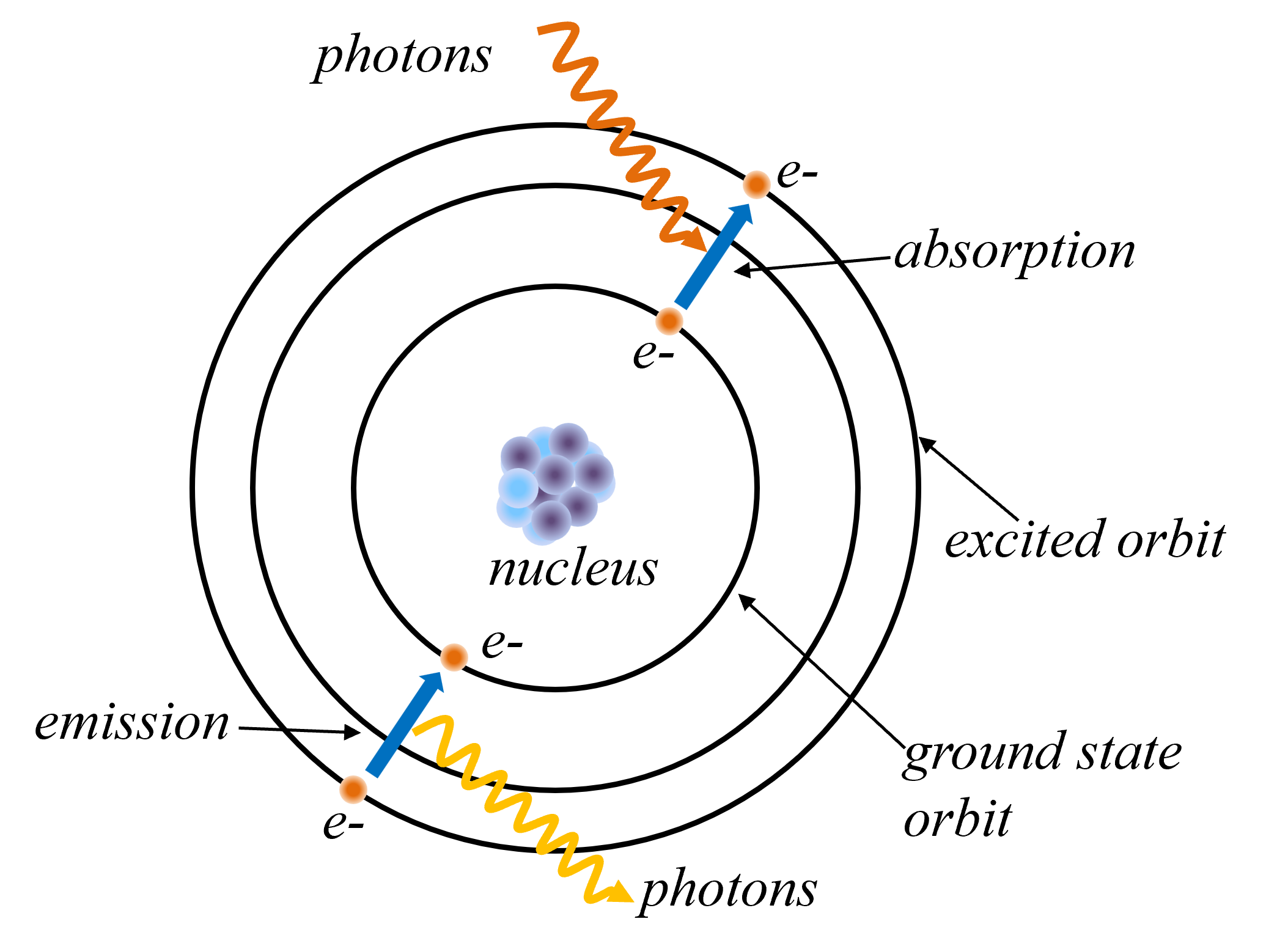

Atoms are incredibly small, with atomic radii typically ranging from about 0.5 to 2.5 Å. Their diminutive size makes them invisible to the naked eye, and even powerful microscopes struggle to visualize them directly. Atoms are remarkably stable structures, held together by strong internal forces that prevent them from spontaneously breaking apart. They possess a neutral charge, housing both negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons in equal numbers. Interestingly, atoms interact with electromagnetic radiation, emitting and absorbing photons of specific energies.

In the early stages of atomic theory, scientists faced significant challenges in directly measuring atomic properties. Limited experimental techniques and the constraints of classical physics hindered their ability to observe and understand the behavior of atoms and their constituents. By interpreting large-scale property measurements, scientists were able to infer microscopic particle properties, laying the groundwork for a more comprehensive understanding of atomic structure. Let’s revisit briefly the evolution of ideas that have shaped our understanding of matter and atomic .

- John Dalton's Atomic Theory: John Dalton, an English chemist, proposed the first comprehensive atomic theory in the early 19th century. His theory posited that all matter is composed of indivisible and indestructible atoms, which are unique to each element in terms of mass and properties. Atoms of different elements combine in specific ratios to form compounds, and chemical reactions involve the rearrangement of these atoms. Dalton's theory successfully explained the laws of conservation of mass and constant composition, laying the foundation for modern atomic theory.

- Avogadro's Hypothesis : Amedeo Avogadro, an Italian scientist, proposed that equal volumes of gases at the same temperature and pressure contain an equal number of molecules. This hypothesis, initially overlooked, later became known as Avogadro's law and proved to be a cornerstone in the development of modern chemistry. It provided a crucial link between the macroscopic properties of gases and the microscopic world of atoms and molecules, enabling scientists to determine relative atomic masses and molecular formulas.

- Kinetic Theory of Gases : Building on Avogadro's hypothesis, James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann developed the kinetic theory of gases. This theory explains the macroscopic properties of gases, such as pressure, temperature, and volume, in terms of the microscopic behavior of gas molecules. It posits that gas molecules are in constant, random motion, colliding with each other and the walls of their container. The average kinetic energy of these molecules is directly proportional to the temperature of the gas. This theory has been instrumental in understanding the behavior of gases and has had significant implications for various fields of science and engineering.

- Michael Faraday's Contributions : Michael Faraday's groundbreaking work in electrolysis in 1833 provided further evidence for the atomic nature of matter. By studying the relationship between the amount of electric charge passed through a solution and the amount of substance deposited or liberated, Faraday demonstrated the quantized nature of electric charge.

- Discovery of the Electron : J.J. Thomson's cathode ray experiments led to the discovery of the electron. Thomson demonstrated that cathode rays were composed of negatively charged particles, later named electrons. This discovery marked a pivotal moment in the history of atomic physics, revealing the existence of subatomic particles and challenging the long-held notion of the atom as the indivisible building block of matter.

- Rutherford's Scattering Experiment : Ernest Rutherford's famous gold foil experiment in 1911 revolutionized our understanding of atomic structure. His gold foil experiment revealed the existence of a small, dense atomic nucleus. This experiment showed that most of an atom's mass is concentrated in its nucleus, with electrons orbiting around it. This groundbreaking discovery overturned the prevailing plum pudding model and laid the foundation for modern atomic theory.

- Bohr's Atomic Model : Niels Bohr proposed a revolutionary model of the atom in 1913. In his model, electrons orbit the nucleus in specific, quantized energy levels. When an electron transitions between energy levels, it emits or absorbs electromagnetic radiation in the form of discrete wavelengths of light. This model successfully explained the observed line spectra of hydrogen and other simple atoms, providing a significant step forward in our understanding of atomic structure and the behavior of electrons.

In the following sections, we will explore Faraday’s pioneering work in electrolysis, Thomson’s discovery of the electron through cathode ray experiments, Rutherford’s revolutionary scattering experiment, and Bohr’s quantum model of the atom

4.2 Faraday’s Experiment

Michael Faraday’s groundbreaking work in electrolysis in 1833 provided compelling evidence for the atomic nature of matter. By studying the relationship between the amount of electric charge passed through a solution and the quantity of substance deposited or liberated, Faraday demonstrated the quantized nature of electric charge. This discovery suggested that electric charge, like matter, is composed of discrete units, a concept foundational to the later development of atomic theory.

Faraday’s experiments led to the formulation of two fundamental laws of electrolysis:

\[\begin{equation*} m \propto \text{Quantity of Electricity (Q)} \end{equation*}\]Faraday’s First Law of Electrolysis: The mass of a substance deposited at an electrode is directly proportional to the quantity of electricity passed through the electrolyte.

Faraday’s Second Law of Electrolysis: When the same quantity of electricity is passed through different electrolytes, the amounts of substances deposited are directly proportional to their equivalent weights.

Faraday’s results may be given in equation form as:

\[\begin{eqnarray} m = \frac{Q * M}{F \ \text{n}} \tag{4.1} \end{eqnarray}\]where:

- m is the mass of the substance substane (in grams),

- Q is the total charge passed (in coulombs),

- M is the molar mass is in grams, and the valence is dimensionless,

- n is the number of electrons transferred per ion (valence),

- F is the Faraday (~ 96,485 coulombs per mole of electrons).

This quantitative framework not only confirmed the discrete nature of electric charge but also laid a foundation for the scientific understanding of electrochemical reactions. Faraday’s contributions remain pivotal in modern chemistry and physics, influencing the study of matter and its interactions at the atomic and molecular levels.

4.3 Thomson Cathode Rays Experiment

The development of vacuum pumps in the 17th century laid the groundwork for investigating the behavior of matter and energy in low-pressure environments. In the 18th and 19th centuries, scientists began to experiment with electricity in these conditions, observing intriguing phenomena such as electrical discharges and luminous glows.

In 1838, Michael Faraday made a significant observation: when a high voltage was applied across a low-pressure gas-filled tube, a strange luminous arc formed between the electrodes. This phenomenon, known as a gas discharge, would become the basis for further investigations into the nature of matter and electricity.

Building upon Faraday’s work, scientists like William Crookes and Johann Hittorf further refined the experimental setup by creating low-pressure gas discharge tubes, often referred to as Crookes tubes. By reducing the pressure within these tubes, they were able to observe distinct cathode rays emanating from the negative electrode. These rays were found to travel in straight lines, cast shadows, and exhibit other properties that suggested they were composed of particles rather than waves. At the time, the nature of these rays was a mystery, with their mass and negative electrical charge unknown. There was a longstanding debate about whether these rays were particles or waves.

In 1897, British physicist J.J. Thomson utilized a cathode ray tube, depicted in the figure, to investigate mysterious rays emitted at low pressure. Thomson and his colleagues demonstrated that these rays consisted of particles significantly lighter than hydrogen atoms, the lightest known element. The trajectory of a charged particle can be altered by applying electric or magnetic fields.

As shown in Thomson’s experimental schematic, applying an electric field between the plates deflects the particle upwards. Conversely, applying a magnetic field perpendicular to the plane of the page deflects the particle downwards.

Thomson determined the velocity of this charged particle by balancing the magnetic and electric forces acting upon it. This technique, guided by the principles of the Fleming left-hand rule, allows for the determination of the direction of the magnetic force.

Let’s delve into the physics underlying Thomson’s Experiment. Initially, we consider the electric field between the plates

The velocity in x direction, \(v_x,\) remains constant because no force acting in that direction. In y-direction, the electron experiences a constant upward acceleration due to the electric force. Since the initial velocity in the y-direction is zero, we have:

\(\begin{equation} v_y = a_y t \tag{4.2} \end{equation}\) The acceleration in y-direction, \(a_y\), is given by:

\[\begin{eqnarray} a_y &=& \frac{F}{m_e} = \frac{E e}{m_e} \nonumber \\ a_y &=& \frac{V e}{m_e d} \tag{4.3} \end{eqnarray}\]where \(F = E \ e\) is the electric force on the electron due to the electric field E and its charge \(e\).

The time taken to travel through the plates is: \(\begin{equation} t =\frac{\ell}{v_x} \tag{4.4} \label{eq:4-4} \end{equation}\)

Combining these equations, we get the velocity in the y-direction after the plates:

\[\begin{equation} v_y = \frac{V \ell e}{m_e * v_x * d} \tag{4.5} \end{equation}\]We also know that:

\[\begin{equation} \tan \theta = \frac{v_y}{v_x} = \frac{V \ell}{v_x^2 d} \left(\frac{e}{m_e}\right) \tag{4.6} \end{equation}\]For small deflection, \(\tan \theta \approx \theta\), so we have:

\[\begin{equation} \theta \approx \frac{V \ell}{v_x^2 d} \left(\frac{e}{m_e}\right) \tag{4.7} \label{eq:4-7} \end{equation}\]Here, \(\theta\) (beam deflection), \(V\) (voltage between horizontal plates), \(d\) (spacing), and \(\ell\) (length) can all be measured. Thus, one only need to measure \(v_x\) to determine \(e/m_e\).

Thomson determined \(v_x\) by applying a magnetic field B and adjusting it to balance the deflection caused by the electric field.

By balancing the magnetic and electric force:

\(\begin{eqnarray*} F_E &=& F_B \\ qE &=& q v_x B \end{eqnarray*}\) or \(\begin{equation} v_x = \frac{E}{B} = \frac{V}{d B} \tag{4.8} \label{eq:4-8} \end{equation}\)

Substituting this expression \(v_x\) (Eq~\eqref{eq:4-7}) into the equation \eqref{eq:4-8} for \(\theta\), we find: \(\begin{equation} \frac{e}{m_e} = \frac{V \theta}{B^2 l d} \tag{4.9} \end{equation}\)

The currently accepted value of \(e/m_e\) is \(1.758803 \times 10^{11} C/kg\). Thomson’s original value was about \(1.0 \times 10^{11} C/kg\), which was a significant achievement considering the limitations of the experimental techniques at the time.

From his cathode ray experiments, Thomson arrived at the following conclusions

From cathode ray experiment, Thomson came to following conclusion:

- Discovery of a Subatomic Particle: By comparing the charge-to-mass ratio of the cathode ray particles to that of hydrogen ions, Thomson concluded that these particles were significantly lighter, approximately 1800 times less massive than a hydrogen atom. This groundbreaking finding marked the discovery of the electron, the first identified subatomic particle.

- A Glimpse into the Subatomic World: Thomson’s work provided humanity with its first glimpse into the subatomic world, revealing the existence of particles smaller than atoms.

- Charge Quantization: Two years after Thomson’s discovery, researchers reported that charges emitted from zinc illuminated by UV light, as well as those produced by ionizing X-rays and radium emissions, were quantized. These charges had values around \(2.3 \times 10^{-19}\) C and \(1.1 \times 10^{-19}\) C, respectively.

- Electron Charge: Particles emitted from various gases subjected to electrical discharges were found to be identical to those observed in the photoelectric effect. This suggested the fundamental nature of these particles. The magnitude of the charge carried by the electron, denoted as , was established as the fundamental unit of electric charge, equal in magnitude to the charge of a single proton.

4.4 Atomic Model

4.5 Spectral Lines

The development of atomic theory was shaped by centuries of experimentation and theoretical speculation by physicists and chemists. Scientists observed that atomic radiation can manifest as either continuous or discrete (line) spectra. This section will delve deeper into discrete spectra, which played a pivotal role in our understanding of atomic structure.

The figure illustrates the discrete emission lines from various elements. When light passes through a dispersive medium, such as a prism or a diffraction grating, it is separated into its constituent wavelengths, resulting in a discrete line spectrum.

Similarly, when atoms absorb light, dark lines appear superimposed on a continuous spectrum at specific wavelengths corresponding to the absorbed light. While the interpretation of emission and absorption spectra for complex atoms can be complex, this course will primarily focus on the simpler case of hydrogen.

Let’s recall the major break through over years on atomic emission and absortion to understand the atomic structure.

- Blackbody radiation: glowing solids, liquid, and even gases exhibit common shape of intensity over wavelength. The peak (highest intensity) in this curve shift toward shorter wavelengths with increasing temperature.

- In 17th century, discrete bright lines (emission) observed a low-pressure gas subject to an electric discharge.

- New elements(Rb and Cs) were identified using emission lines by Gustav Robert Kirchhoff and Robert Wilhelm Von Bunsen. They determined the new elements via observing new sequence of spectral lines in mineral samples.

- Fraunhofer observed 1000 fine dark lines (first absorption spectrum) when continues sun light pass through narrow slit and then disperse through a prism.

- Kirchoff explained Fraunhofer's dark D-lines in the solar spectrum using absorption which was the major contribution for the spectroscopy.

Kirchhoff successfully showed that presence of sodium vapor in the solar atmosphere via observing dark lines from Na vapor where those lines exactly match in wavelength with Fraunhofer dark lines. Here, D-lines darken noticeably when sodium vapor in introduced between the slit and the prism